The Cost of Summer

An inside look into the operating budgets of high-quality summer learning programs in California

Executive Summary

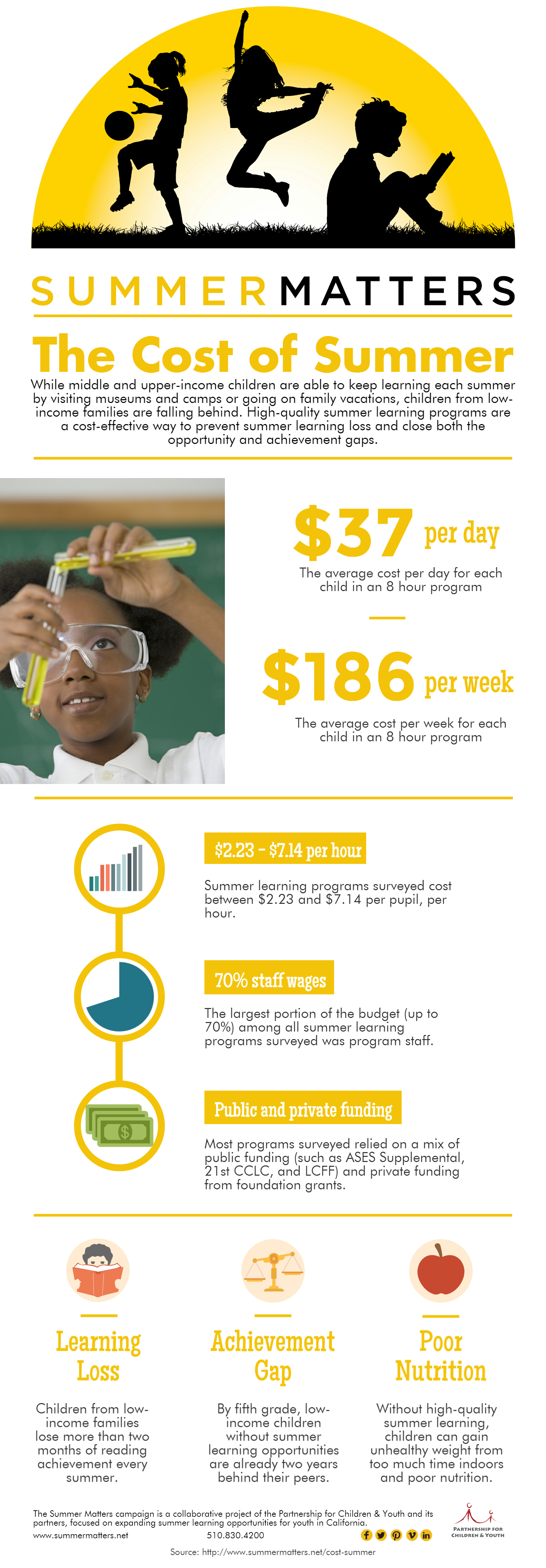

Summer can be a costly time for low-income families. According to Jennifer Peck, Executive Director of the Partnership for Children and Youth, “While middle-income children retain knowledge or, in many cases, make gains over the summer, low-income children fall behind.” Summer learning programs are a cost effective way to prevent summer learning loss and close the opportunity gap. In order to better understand the cost of such investments, Summer Matters conducted a small survey of partner organizations offering high-quality summer learning opportunities in California.

Key Findings:

- Summer learning programs surveyed cost between $2.23 and $7.14 per pupil, per hour. At eight hours per day, each student served by these programs cost an average of $37.15 per day or $185.77 per week, at five days per week.

- The largest portion of the budget (up to 70%) among all summer learning programs surveyed was program staff.

- Most programs surveyed relied on a mix of public funding (such as ASES Supplemental, 21st CCLC, and LCFF) and private funding from foundation grants.

According to the Afterschool Alliance, parents in California reported paying an average of $307 per week for summer learning programs, which is out of reach for many families. “Our students from low-income families start school from behind and they never catch up,” said Ron Carruth, superintendent of the Whittier City School District. “Unless we have engaging opportunities for students in the summer, we’re never going to help them close the gap.”

Summer Learning Loss Facts

- Children from low income families lose more than two months of reading achievement every summer.

- Summer learning loss explains two-thirds of the ninth grade achievement gap.

- By fifth grade, low income children without summer learning opportunities are already two to three years behind their peers.

- Without high-quality summer learning opportunities, children can gain unhealthy weight from too much time indoors and poor nutrition.

High-Quality Summer Learning Programs

Summer learning programs are more than traditional summer school. “We’re trying to create an opportunity that falls in between the boring remediation model of traditional summer school and the fun of a summer camp,” explains Katie Brackenridge, Vice President of Programs at the Partnership for Children & Youth. “It’s that sweet spot—called summer learning—where they’re having a great time and they’re also intentionally learning something through those activities.” The After School Program Coordinator for Glenn County Office of Education, Philip James said, “Prior to 2012, programs were typically identified as summer school. They were primarily for remediation and consisted mostly of practice drills and direct instruction. Typically they were seen as a punishment. We wanted to find a way to motivate, engage, and reach more students.” Summer school used to be “more like tutoring,” said Becky Schultz, Whittier’s Director of Expanded Learning. “And it really didn’t work, sitting there all day long in a math class. It’s really changed now, and I hope we never go back.”

Current Research

In 2009, the Wallace Foundation published a then groundbreaking report, “The Cost of Quality,” detailing the costs of strong afterschool and summer programs. After a detailed examination of 111 high-quality afterschool and summer programs, they determined several key findings:

- The cost variables stem from program factors such as program hours, youth-staff ratios, age groups served, and types of facilities.

- Per-child costs in larger programs are not necessarily less expensive than those in smaller programs.

- In 2015 dollars, the daily per-slot cost of high-quality after school programming for elementary and middle-school children ranged from $14 to $31.

- Expanding after school or summer program size to include more children can produce economies of scale, but only up to a point. Past a certain threshold, high-quality programs hire more staff members, which increases costs.

- Although most costs in high-quality after school and summer programs are covered through out-of-pocket expenditures, in-kind contributions are an important source of funding for many programs. For example, many school districts that partner with community based organizations do not charge their partners for use of otherwise empty school facilities during the summer.

The “Cost of Quality” has been a valuable resource for estimating the cost of after school and summer programs. Summer Matters seeks to expand on these findings as they relate to summer learning programs in California.

Six Signs of a Great Summer Learning Program

Some readers may ask how Summer Matters defines program quality. Six key elements of an effective summer learning program, and what they mean in practice, are the following:

- Broadens youth horizons by exposing them to new adventures, skills, and ideas such as a nature walk, new computer program, museum visit, or live performance.

- Includes a wide variety of activities such as reading, writing, math, science, arts and public service projects – in ways that are fun and engaging.

- Helps youth build mastery by improving at doing something they enjoy and care about, such as creating a neighborhood garden, writing a healthy snacks cookbook, or operating a robot.

- Fosters cooperative learning by working with their friends on team projects and group activities such as a neighborhood clean-up, group presentation or canned food drive.

- Promotes healthy habits by providing nutritious food, physical recreation, and outdoor activities

- Lasts at least one month giving youth enough time to benefit from their summer learning experiences.

Methodology

The survey conducted by Summer Matters provides only limited confirmation of the findings of more robust academic studies, such as the “Cost of Quality.” The Summer Matters survey relies on a relatively small sample size of only ten programs. “We were not seeking to replicate the Wallace Foundation study,” said Brackenridge “Rather, we hoped we might be able to see how their findings applied to programs we already know a lot about. Each of the organizations we surveyed are our partners, and we know first-hand that they offer high-quality programs.” Summer Matters surveyed ten organizations operating programs during the summer of 2015 in six counties: San Francisco, Alameda, Los Angeles, Santa Clara, Santa Barbara, and Glenn.

The survey included questions about:

- program design

- number of days

- hours of operation

- number of sites

- number of students served

- funding sources

- program budgets (including direct spending and in-kind contributions, in five categories: staff, administration, transportation, facilities, and other)

Not all respondents were able to provide the same data points and each program organizes their budget differently, making it difficult to align categories of spending or distinguish between costs associated only with summer and those related to services provided during the school year.

Key Findings

The results of the survey indicate that operating summer programs in California may be more costly than national averages, and that within the small sample size, some economies of scale were achieved. Otherwise, findings were in keeping with the Wallace Foundation study.

The average cost per student was $37.15 per day or $185.77 per week.

Programs we surveyed cost an average of $185.77 per week to operate eight hours per day for five days per week. This is higher than the national average, but significantly lower than the average amount parents in California report paying in fees.

The range of costs (per pupil, per hour) was $2.23 – $7.14

After adjusting for variations such as costly fundraising strategies or year round programming, the hourly cost per child was between $2.23-7.14. The most significant driver of cost was the number of students served.

The largest cost was staff

Program staff wages were reported as the largest portion of spending among all programs surveyed. With increases in the cost of living over time, stagnant public funding may represent a significant challenge in the future.

Programs use a mix of public and private funding

Most programs surveyed relied on a mix of public funding and private foundation grants. Typically, public funds for summer learning programs are distributed through After School Education and Safety Supplemental, 21st Century Community Learning Centers, and Local Control Accountability Plans.

Conclusion

Summer learning programs can be more cost effective than traditional summer school. This is primarily due to the mix of certificated and classified staff members in summer learning programs. Partnerships between school districts and community-based organizations are also an essential strategy that contributed to cost effective program designs. While the majority of funding for summer learning programs comes from public resources or foundation grants, there is no single source of support for summer learning programs. Effective programs utilize multiple sources of revenue to stop summer learning loss.

Learn More About Summer Learning

A wealth of information is available describing the options for funding, organizing and operating a summer learning program that students will love.

Resources

Investing in Summer Learning: Stories from the Field

LCFF: Leveraging Summer for Student Success

Tool: Three Sample Budgets for Summer Learning Programs

VIDEO: Summer Learning: An Inspiring Alternative to Summer School

Acknowledgments

Jennifer Peck, Partnership for Children & Youth

Katie Brackenridge, Partnership for Children & Youth

Daren Howard, Partnership for Children & Youth

Ezra Denney, Partnership for Children & Youth

Stephanie Pollick, Partnership for Children & Youth

Alec Lee, AIM High

Sheryl Davis, Collective Impact

Sara Williams, Collective Impact

Gianna Tran, East Bay Asian Youth Center

Eduardo Caballero, Edventure More

Amanda Reedy, Gilroy Unified School District

Philip James, Glenn County Office of Education

Stela Oliveira, LA’s Best

Ann Marie Johansen, LA’s Best

Julie McCalmont, Oakland Unified School District

G. Paul Didier, United Way of Santa Barbara

Melinda Cabrera, United Way of Santa Barbara

Ron Carruth, Whittier City School District

Becky Shultz, Whittier City School District

Mary Hoshiko, YMCA of Silicon Valley

Jay Dunn, Photographer

Summer Matters is an initiative of the Partnership for Children & Youth (PCY). Learn more about Summer Matters and the many educators, policymakers, school district leaders, organizations, and parents working collaboratively to promote summer learning in California at www.summermatters.net. For more information on PCY, and to learn about all our initiatives, visit www.partnerforchildren.org.

Survey Participants:

- Aim High

- Collective Impact

- East Bay Asian Youth Center

- Gilroy Unified School District

- Glenn County Office of Education

- LA’s BEST

- Oakland Unified School District

- United Way of Santa Barbara County

- Whittier City School District

- YMCA of Silicon Valley

*Edventure More also participated in the survey, but featured a program design that differed significantly from other respondents and was later excluded from the summary data.